AI as the Worst Parasocial Relationship

Except for All the Others (The Era of Machine Learning 2)

A universal experience is being tempted by several things at once. A common example when I was in high school was sugary snacks and video games. I would typically deal with this problem by taking advantage of tradeoffs. I figured that the video games were less harmful to me, so I would distract myself by playing Super Smash Brothers Melee whenever I was too tempted to buy bubble tea or some other sweet. I don’t think that video games were a direct good for my life, but I’m almost certain that my life would have been worse without them. Whether in life, business, or society, it helps to displace problems with lesser problems. This is how I see almost all “short-term” worries about machine learning and relationships.

A typical example is Yuval Noah Harari’s article (paywall-free here, download the html file). Here’s an excerpt:

In a political battle for minds and hearts, intimacy is the most efficient weapon, and ai has just gained the ability to mass-produce intimate relationships with millions of people. We all know that over the past decade social media has become a battleground for controlling human attention. With the new generation of ai, the battlefront is shifting from attention to intimacy. What will happen to human society and human psychology as ai fights ai in a battle to fake intimate relationships with us, which can then be used to convince us to vote for particular politicians or buy particular products?

What exactly does Yuval think is the problem introduced by AI intimacy? Each problem it introduces already exists in ordinary politics, arguably to a worse degree. Are people going to support worse policies because they are being charmed by Sydney rather than Bush, Obama, Trump, or Biden? Is the ideal representative someone with the emotionless affect of Blake Masters? Honestly, that’s a bullet I’m willing to bite. A vote for Blake is a vote against artificial intimacy! (I’m told I’m a bit late with my endorsement.) Equality of charm would lead to smarts and strategy becoming more important, and I think that’s a good thing. It might even solve the Trump problem. From Richard Hanania:

Analysts are finally coming to the realization that this isn’t about trade, immigration, or gender ideology. It’s not about issues at all. There’s simply a deep and personal connection between Trump and the Republican voter.

Or consider concerns over AI-generated porn or sexually explicit chatbots. Maybe it’s possible to argue that due to increased effectiveness, they are displacing real relationships. However, they are much more similar to existing parasocial services like OnlyFans or regular porn, so it's much more likely they displace those. Like old video games, AI vices displace arguably more harmful ones. Impersonation is a more legitimate concern, but unlawful representation of someone’s image is already illegal.

One unifying theme is that when journalists, scientists, or politicians investigate the details of an AI product, they come to a similar conclusion to Part 1 of this series: that AI is much more empathetic than logical. The reactions to this discovery are nearly universally negative. Perhaps this is just a consequence of plain negativity bias and risk aversion, but I don’t think this succeeds in fully explaining the focus on artificial empathy, rather than some of the more reasonable (though in my view still wrong) arguments raised by Effective Altruists. There are two explanations I can give for this, one which focuses on artificial empathy as maladaption and another on political economy.

They’re Right About Disembedded Empathy

People to the social right of me, such as Mary Harrington or Charles Haywood would say that the fault here is the disembedding of empathy from real life personal interactions. Take Haywood’s review of Harrington’s new book, Feminism Against Progress.

We are offered a tour of history, and thinkers from Karl Marx to Karl Polanyi, to show that before the Industrial Revolution, all women outside the upper classes worked. But that work was very differently structured from today. It was, for both women and men, embedded within thick social relationships, both those of the marriage and of larger society.

…

The Industrial Revolution, the first widespread application of technology, destroyed this partnership by exalting the market as the talisman of every man and woman’s worth. The pre-existing roles that women occupied, with honor, in pre-industrial Western society were denigrated, because they were not market-oriented. This was not only a result of technology, however, but also of the ideology that grew like cancer during the Industrial Revolution, the so-called Enlightenment, which among other atomizing demands exalted autonomy-granting measurable economically-productive work, while denigrating the embedded work of care and community, of weaving a society together on every level.

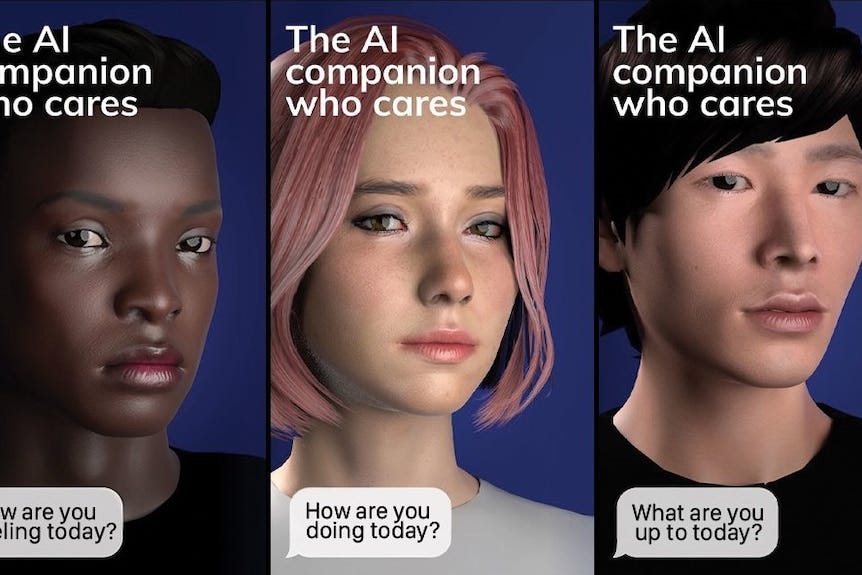

In this view, the original error was industrialization and mass communications. One-to-many communications inevitably made parasocial relationships the norm, in which one person feels like he is in a relationship with a celebrity, viewing hours of that celebrity’s content and feeling a deep personal connection, all while that celebrity knew nothing of the fan in turn. From this perspective, the anger expressed over AI versions of parasocial relationships are an extension of the pent-up anger over liberal atomization. AI is the logical conclusion of their political and moral philosophy, but they can’t really bear to admit it. Instead, they cope by blaming the technology, which doesn’t really contribute anything worse.

Where I likely differ from Haywood and Harrington view is that I believe that even knowing the criticisms they’ve raised, most people would still choose present, atomized conditions over the alternative of strong social bonds and expectations. Convenience is a real preference, even if there are tradeoffs to them. The revealed preferences of people in the real world certainly reflect this (but if they didn’t, no one would be talking about parasocial relationships with AI in the first place). Many people, particularly young people, fear judgement and social expectations. Different measures put the diagnosis of anxiety disorders in Zoomers between nearly 20% and slightly over 30%, with many Zoomers falling below the bar for a clinical condition but still suffering from some symptoms. Parasocial relationships are actually preferable for people like this, since they have no chance of being identified, let alone judged. In this case, AI is even more preferable, since the AI can provide attention and company in ways that celebrities can’t, while still never being able to actually judge someone. There’s two perspectives on this: one is that people with such disorders should be forced to socialize until they’ve hopefully overcome their anxieties and the other is that it’s basically fine for them to remain this way as long as they can still contribute to society. In my anecdotal experience trying to encourage the former typically backfires and the best way to take care of someone with social anxiety is to do the latter, but I’m definitely willing to change my mind on this.

Returning to the establishment liberal position, there is actually some mention of this argument by its proponents. Take this excerpt from Ezra Klein interviewing Erik Davis:

[Ezra:] There is something about how much we have dehumanized ourselves that I think is getting laid very bare in A.I. discourse. If we have such a thin ranking of our own virtues and values that these programs can destabilize it so easily, given how limited they are and probably will be for some time, I think it’s getting at something that is a little bit more discomforting, which is that we have valued human beings very poorly.

And it would take a lot culturally and maybe call a lot that we have done into question to value ourselves and other creatures in the world differently. But if we don’t, then we actually have no defense against at least the psychic trauma of this thing we’re creating, which is aimed right at our own definition of intelligence.

ERIK DAVIS: Yeah, my reaction to that is to immediately think about animals. Because it’s not coincidental perhaps. It’s sort of very interesting that just at the point where we’re wrestling with this question of machine intelligence and whether we can call it intelligence or not, we are just getting more and more proof that our definitions of human difference don’t stand up to the realities that animals live in, that they are.

And the different reactions that that brings up — and I’m thinking in terms of animals — is that exciting? Are we happy to welcome a much wider sense of cognitive potential and to willingly step down from the throne? Is it threatening because of all of the moral issues that it raises, particularly in terms of how we treat animals and the horrific extinction rate that we face in the planet?

A slight aside: This type of reaction is somewhat why I view Democrats as the stupid party. Here is an obvious example of a tool that is smarter than some humans and not others and the immediate jump is to animals (which they also approach in slave morality terms). As I’ve discussed on my podcast with Erik Torenberg, GPT4 is an unmistakable waterline showing that some people are smarter than others and to deny this is far more delusional than anti-vax or Stop the Steal. You can interpret the latter as inability to observe some distant fact, but the failure to observe immediate, close-up facts has always seemed to me to indicate the most stupid groups of people. A psychoanalysis that I don’t think applies to the best AI risk proponents but certainly to some of the mediocre ones is that they just can’t cope with this clear waterline. They have to believe that some essence of AI makes it either dumber than all humans or smarter than them. The reality is that there is a huge range of human ability, some are capable of nothing that GPT2 can’t do, some still far surpass GPT4.

The Political Economy of Fake Empathy

To take the Harrington view again — which I see as the “legitimate” counterargument to my position, the one that is self-consistent and correct about the facts, but with different moral premises — we have disembedded a lot of processes from the social systems and contexts which people evolutionarily enjoyed and pursued. There is something in speaking with someone personally, in a packed room, or over dinner, that drastically changes the experience. What I take aim at is this intermediate position that AI is the line that’s too far. If you have porn, Twitch streamers, OnlyFans, etc. you’ve already done the disembedding. You’ve already created the world in which people prefer fake empathy to embedded empathy, AI just cuts out the middlemen.

This brings us to the more cynical interpretation, which is that the Harari-style cope is because they can no longer be the center of attention. They were doing some very profitable rent-seeking, taking advantage of their ability to project this style of fake empathy to the online masses, and are simply angry that the AI is better than them at it. There is honestly not much to say about this other than the fact that it lines up with the historical pattern of Luddism and regulation. Ironically, Harari compares AI to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave:

In the 17th century René Descartes feared that perhaps a malicious demon was trapping him inside a world of illusions, creating everything he saw and heard. In ancient Greece Plato told the famous Allegory of the Cave, in which a group of people are chained inside a cave all their lives, facing a blank wall. A screen. On that screen they see projected various shadows. The prisoners mistake the illusions they see there for reality.

Instead of creating the shadows, LLMs let people know there is a world outside the cave. And like in Plato’s cave, many people refuse to believe it.

Equilibrium

The horseless carriage fallacy refers to the common mistake of imagining a society adopting a technology but changing nothing else about its norms. The name refers to a common term for early cars, “horseless carriage”. Of course, a car did much more than replace the carriage; it allowed the development of cities and suburbs at a scale otherwise impossible, scaling business and technology along the way. What’s interesting about the current period is that there is a kind of horseless carriage fallacy of the present happening with the word empathy, where it has shifted from meaning in-person, time-bound connections to something that can be expressed by an anonymous corporate statement. Empathy has been replaced with parasociality, and AI is here to give the highest possible quality of parasociality possible. I’m typically a strong believer in self-deception, but I think the degree of separation between parasociality and real empathy is so clear and undeniable that a distinction between the two has to re-emerge. In this way, the parasociality of AI is far more healthy than the parasociality of twitch streamers and celebrities.

“But Brian, you haven’t answered the most important question of all! Will people want the real empathy or not?”

Honestly, I’m not sure. I think there will be people who want the real thing and people who are fine with the parasocial version. I don’t have a clear guess at what proportion of the population each will be. The only thing I’m confident about is that people will begin to notice the difference.

So is this like a "harm reduction" approach to relationship facsimiles? You can't get them off the drug entirely, but can at least give them clean needles.

Think I'm with Harrington.

The main difference is not *who* wins the profits of the parasocial relationship competition (honestly, why would anyone outside that game care about that?), but just about the relative power of ParasocialAI versus anything manageable by real people.

Think drugs more than parasocial relationships; something where revealed preferences might not be real preferences due to human weakness against adversarial inputs. For many people, drugs make their life worse in most ways, but they are not free to get rid of them. Of course, some people who can easily try out some drugs and stop, but most people never try the drugs at all. Note that in case of drugs, there are many factors for why people don't try them (in addition to drugs being commonly understood as bad things, *creating and dealing drugs is a crime* in most non-US locales), none of which apply in the AI case.

Now to preempt the obvious reply: my values definitely include many people vulnerable to drugs, but even if your values do not extend to people that are too weak to fight off drugs, there's no real guarantee that ParasocialAI harms the same set of people. Chemical channels surely enable more control over the human body than audiovisual/text channels do, but AI can be optimized much more; and also it's infinitely easier to give someone a taste of ParasocialAI than to make them take some drug.

As for when any of this is relevant... who knows. I would bet a not-too-large amount of money on parasocial relationships being one of the easier things to be very superhuman at? Not sure how to formalize the bet, because there are large cultural incentives against actually doing this.