The recent NTIA Artificial Intelligence Accountability Policy Report is a warning shot to AI ecosystem developers. The report proposes a future that threatens to impose new compliance costs and higher barriers to entry without articulating how these costs help advance NTIA policy goals for a large fraction of affected developers. Instead, we encourage an evidence-based approach to AI policy, prioritizing points of intervention that are likely to lead to their stated policy goals, rather than one that makes as many interventions as possible.

In “Section 2.3: ENSURE ACCOUNTABILITY ACROSS THE AI LIFECYCLE AND VALUE CHAIN”, the NTIA targets programmers at every stage of AI development for regulation. This “kitchen sink” approach to regulation proposes a wide spectrum of interventions, without articulating how they address the stated harms identified in the report. This threatens large parts of the startup ecosystem who adapt foundation models to specific tasks through fine tuning, prompt engineering, other infrastructure, optimizations on inference, or other intermediate processes. The NTIA’s proposal endangers contributions to state-of-the-art research, widely adopted developer tools, identification of vulnerabilities in larger systems, and provides many other downstream benefits. By imposing completely unnecessary fixed costs on these developers, it will limit competition in the field when it is needed most, further reinforcing the existing concentration of power in a small number of large companies.

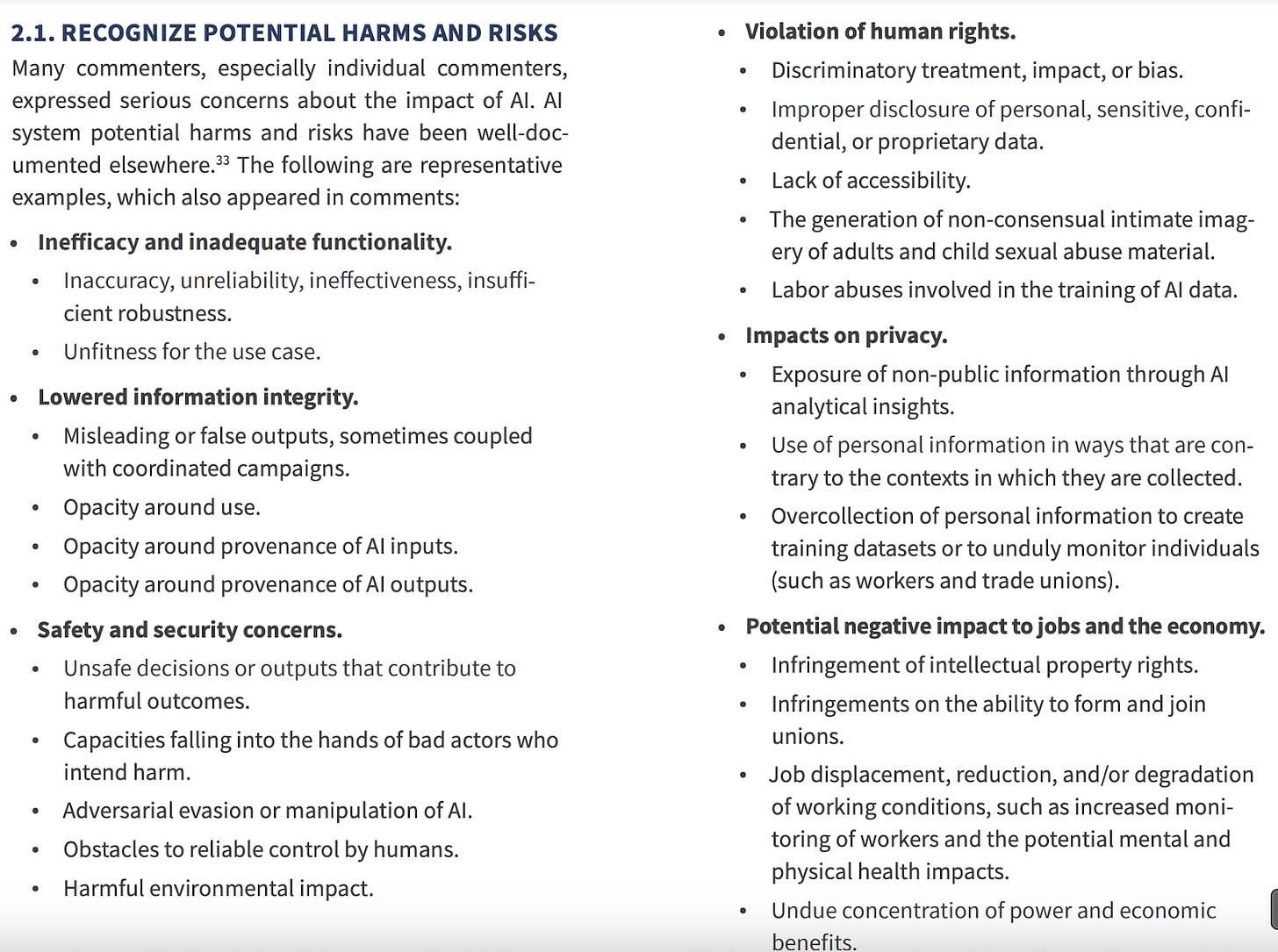

In section 2.1, the NTIA outlines six categories of potential harms and risks. “Opacity around provenance of AI inputs”, “labor abuses involved in the training of AI data”, the “Impacts on privacy” section, and “infringement of intellectual property rights” specifically address training data. All other categories specifically address the final consumer-end product, aside from possibly “obstacles to reliable control by humans”. To effectively address these harms, policy proposals should focus exclusively on user-end deployment and training data (which the NTIA refers to as “inputs”, a term typically used in industry to describe a user’s input to an already trained and published AI model). This approach would address the vast majority of the NTIA’s identified harms and risks while also avoiding harming a large fraction of the startup ecosystem.

The NTIA’s argument for the “kitchen sink” approach to AI regulation is primarily that developers in different stages have access to different information.

“Commenters laid out good reasons to vest accountability with AI system developers who make critical upstream decisions about AI models and other components. These actors have privileged knowledge to inform important disclosures and documentation and may be best positioned to manage certain risks. Some models and systems should not be deployed until they have been independently evaluated.41

At the same time, there are also good reasons to vest accountability with AI system deployers because context and mode of deployment are important to actual AI system impacts.42 Not all risks can be identified pre-deployment, and downstream developers/deployers may fine tune AI systems either to ameliorate or exacerbate dangers present in artifacts from upstream developers. Actors may also deploy and/or use AI systems in unintended ways.

Recognizing the fluidity of AI system knowledge and control, many commenters argued that accountability should run with the AI system through its entire lifecycle and across the AI value chain,43 lodging responsibility with AI system actors in accordance with their roles.44 This value chain of course includes actors who may be neither developers nor deployers, such as users, and many others including vendors, buyers, evaluators, testers, managers, and fiduciaries.”

It is true that there is differential access to information at various stages of development, but that does not imply that access to this information meaningfully contributes to the NTIA’s identified policy goals. For large parts of the value chain, from after the training of the initial foundation model up until just before user deployment, the report does not present a single argument that policy intervention would address any of its identified harms or risks.

Needlessly intervening in intermediate stages of development represents a dangerous approach to policy making: one that treats the expansion of the regulatory domain as costless or even a priori good. This approach will needlessly strain developers and even regulators themselves. Developers, particularly ones in smaller firms, are harmed by imposing additional compliance costs. Regulators have limited resources. Leading them on a wild goose chase with no identifiable contribution to their desired policy outcome reduces the time available to work on points of intervention which do contribute to these outcomes.

Certainly, regulation at the endpoints of training data and user deployment require strategic evaluation of costs and benefits. However, narrowing the scope of intervention for NTIA would be a powerful first step in developing a coherent and strategic approach to AI policy. Furthermore, determining specific points of interventions and policies which have a direct causal influence on the targeted harms and risks can further narrow the unnecessary harm to developers while addressing the underlying concerns more effectively.