Hardware is Centralized, Software is Decentralized

The EA paper you people wanted me to cover

Many people have messaged me about a new paper the Effective Altruists have put out. It mainly summarizes topics already covered in this newsletter. Still, it’s useful to go over many of the same facts and point out that once again, there’s broad agreement over what is vulnerable to regulation. Near the end, I write a bit about the importance of compromise over material tradeoffs (as opposed to norms or ideals), as well as why I think compromise between EAs and accelerationists makes sense in an ideal but not in practical legislative politics.

Hardware is Easy to Restrict

Here’s the most important quote from the abstract:

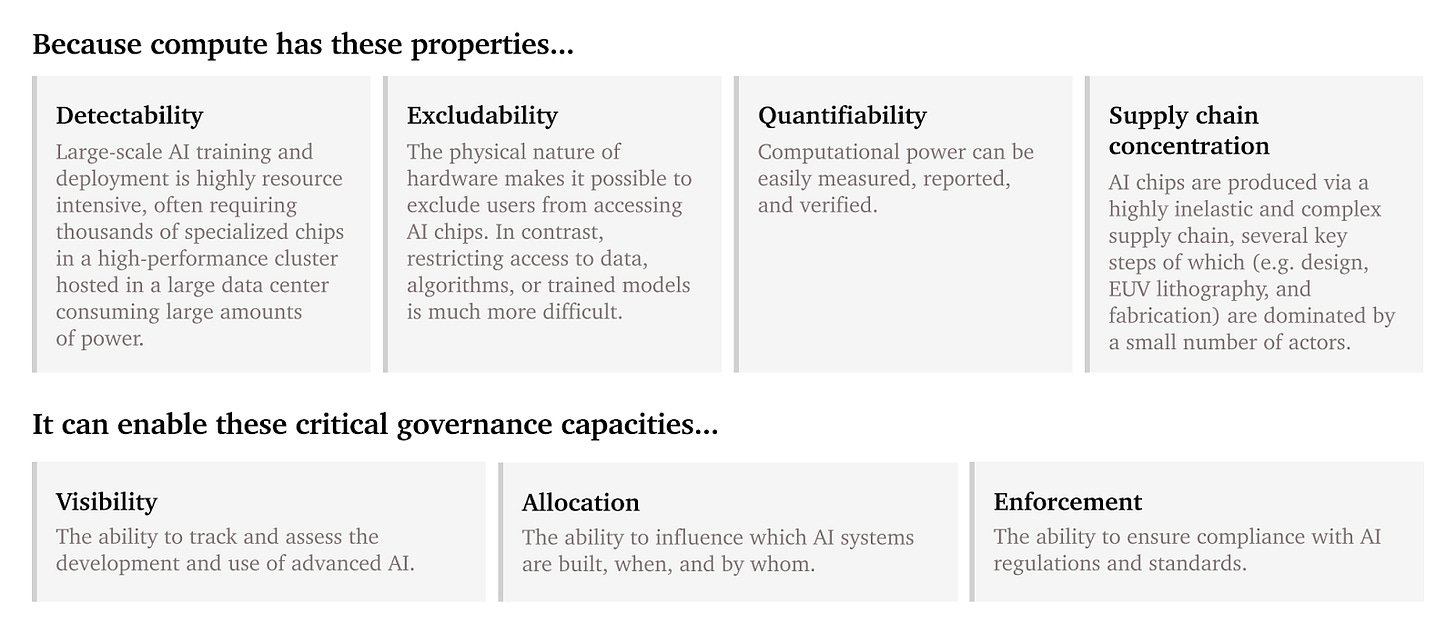

Relative to other key inputs to AI (data and algorithms), AI-relevant compute is a particularly effective point of intervention: it is detectable, excludable, and quantifiable, and is produced via an extremely concentrated supply chain. These characteristics, alongside the singular importance of compute for cutting-edge AI models, suggest that governing compute can contribute to achieving common policy objectives, such as ensuring the safety and beneficial use of AI. More precisely, policymakers could use compute to facilitate regulatory visibility of AI, allocate resources to promote beneficial outcomes, and enforce restrictions against irresponsible or malicious AI development and usage.

Most of the paper is summarized by this one chart. I have to say, their charts are very nice.

The two main takeaways:

Hardware procurement is the most traceable and most vulnerable to interference, for better or for worse

Given the amount of existing hardware, full crackdowns on AI will require orders of magnitude more force than partial crackdowns on hardware

I’ve gone over this in more detail in my coverage of the more infamous EA paper. Both are obvious, but worth reiterating. It should flow very naturally from your practical sense of how hard it is to get something. Getting a GPU, a physical object requires making an order through Amazon. Getting a lot of GPUs requires striking a deal with one of two or three major suppliers. Further up the supply chain, there are even more bottlenecks, such as TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company). Alternatively, you can go through a cloud provider, but that only offsets the burden of acquiring hardware onto them. Meanwhile, data is sourced from the internet and other public databases in most cases and algorithms are developed in house or copied from research papers online. Another great chart from the paper:

EAs and accelerationists alike use “algorithms” to describe the third component, but really something like “research” better fits the bill. Writing faster CUDA kernels is more software than hardware, but it’s not a change in the algorithm akin to going from RNNs to transformers. In either case, this is something published in the open or done by in-house engineers. More importantly, “Algorithms'' makes the thing we’re talking about more opaque to the average person. When people talk about regulating “algorithms” in the context of machine learning, they mean telling people the government will arrest them if they publish research papers or code online. It’s not legally or politically feasible save for some truly extreme and novel interpretations of presidential authority.

Effective Altruists Do Not Want To Stop At Hardware

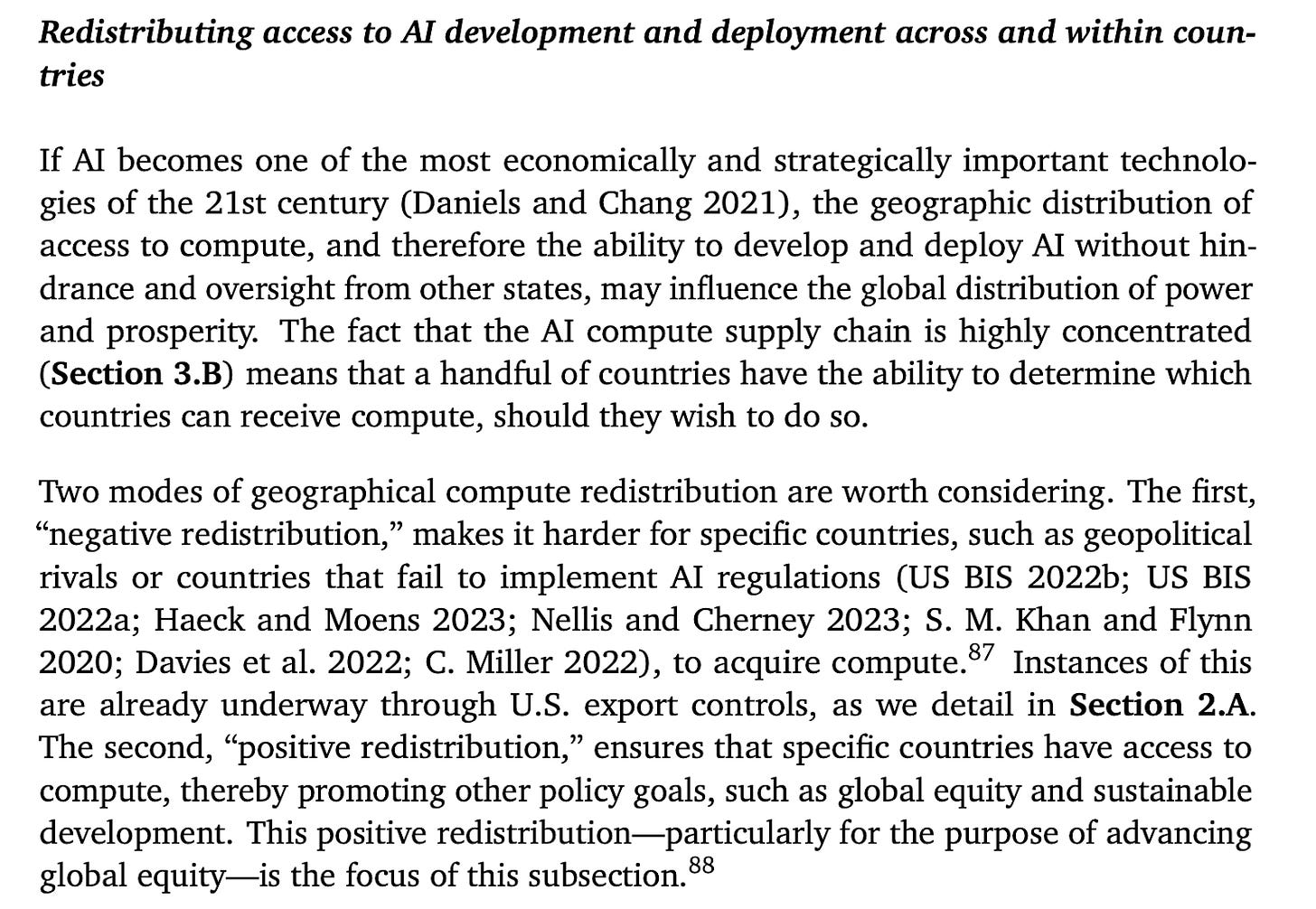

Returning to the paper, most of section 3 is repeating the first chart with different analogies and examples. Paying attention to the first chart is all you need. Near the end there’s another interesting quote:

We expect that regulation of AI deployment will be a part of any frontier AI regulatory regime. However, we argue that without regulations on the development of AI, regulation on AI deployment would not be adequate to protect against the most severe risks from AI, due to (at least) two key shortcomings (Heim 2023a; Anderljung, Barnhart, et al. 2023; Kolt 2023; Matheny 2023).

First, it will be very difficult to identify all relevant deployments of any given model

with high reliability. Individual copies of a model can be run using a relatively small

amount of compute, making it extremely difficult to detect which computers they’re

being run on. Copies can also easily be distributed to many different actors—for

example, via sharing the weights online. Even models whose weights aren’t released

publicly, such as GPT-4, could be stolen via hacking or insider espionage, then deployed

by the attackers

It reiterates a few points from the other papers. Important notes:

As the paper covers and I agree with, restrictions on hardware are by far the most feasible without severe overruling of constitutional authority and individual rights. Moreover, objective measures like total FLOPs (FLoating point OPerations) make it possible to implement hardware restrictions that apply fairly to all companies, rather than a license process or centralized agency that incentivizes double standards that bolster legacy companies and harm smaller startups.

With that in mind, the most concerning sentence in the above section is the first. Similar to the previous paper I covered, much of this paper goes into precise detail about how much total surveillance and control over engineers and researchers is necessary to implement restrictions on software or published models. The expectation or even endorsement of extreme measures, which the authors agree upon in no uncertain terms to be extreme measures in the same block quote, is highly dangerous.

Compromise with EAs is Good, Actually

The importance of compromise on material grounds is driven by two factors. Knowledgeable people often steelman the anti-AI coalition by focusing on effective altruists. This can be done intentionally, out of decorum. It can also be done because arguing with other parts of the anti-AI coalition is simply restating basic facts which quickly disprove their points ad nauseum. Even this article is arguably part of the problem.

While I disagree with EAs’ conclusions, a much greater degree of specificity and explanation of domain knowledge is required to counter their arguments. On the other hand, the likes of socialists, race-grifters, special interests, and mistanthropes will make arguments easily debunked in a few minutes of using the technology they demonize, such as ChatGPT, Gemini or DALL-E. They’re just as likely to make arguments that are clearly wrong or contradictory even if you don’t know anything about the underlying technology. As a result, you might think that effective altruists would represent a more politically powerful part of the anti-AI coalition. Unfortunately, politics is not a meritocracy. Accumulated special interests can wield far more power while being far less rational. So this focus is sometimes unwarranted. There are areas in which EAs wield more power, particularly when it comes to influencing current AI companies. However, that’s beyond the scope of this article.

I continue to genuinely believe that while many EAs are willing to severely restrict individual freedoms in order to avoid what they see as a potentially humanity-ending AI, the restriction of freedom is only a means to an end. However, many other special interests have the restriction of freedom as the end, and only see AI policy as a means. If it is possible to come to a material compromise between smart, reality-focused people, this is by far a better compromise than what the anti-AI coalition left on its own is likely to produce.

Capitulation to Special Interests

Unfortunately, that does not appear to be the direction the authors of this paper seek to move in. Section four is likewise mostly a restatement of the second half of the first chart. Here is a similar chart at its start.

At this point, I think moderates, libertarians, and conservatives all have an understanding of what is happening when someone tries to set up a registry. It’s rarely the case that a state demands meticulous documentation of something and then leaves it alone. There’s a Seeing-Like-a-State equivalent to Chekhov’s gun: if a state demands omniscience into an area it will inevitably demand omnipotence over it. What exactly would be done with the registry? Would it be narrowly focused on prevention of unaligned AGI?

Section four is concerning in a different sense, in that it shows effective altruists capitulating to self-destructive special interests more likely to misalign AI than align it. Ultimately, despite believing Effective Altruists are wrong on crucial facts, I believe they typically try to come up with good faith solutions to their problems. The same cannot be said for a majority of the suggestions in this section.

This is literally just central planning. This is the part of the paper where the EAs veer off into sheer corruption and supporting of Democratic party special interests that have no relationship whatsover to preventing unaligned AGI. There really is no other way to put it. The policy is using the American government to pay for GPUs for organizations which lobby the American government. There is really only one way a self-respecting EA who cares at all about evidence would unironically say this is a good idea is if their logic is “favoring stupid central planning policies will allocate resources poorly and slow the pace of AI development as a result”. I’ve heard EAs give this style of argument before in private, so it’s not completely out of the question that they think that. If that’s the reasoning behind the authors endorsing these policies, they should say so in the paper. Otherwise, it demonstrates an unequivocal capitulation to irrational and economically ignorant special interests. More of the same:

Another proposal is to nationalize the chip supply. Hey, at least they’ll pay the manufacturers.

An alternative possible means of using compute supply restrictions to modulate the pace of AI progress could be a government-operated “compute reserve.” This could first involve government authorities acquiring most or all cutting-edge AI chips produced by leading chip manufacturers. Government acquisition of chips would likely not be via expropriation, but rather via direct purchases at the fair market value of the AI. This would also maintain incentives to build out new fabs, and thereby create the option to more easily increase the flow of compute in the future.

There is no substantive difference between this plan and full-on nationalization. The fact that they are paying the manufacturers does not actually overcome the immense deadweight loss caused by state-run industry. But since they’re trying to slow AI progress, this isn’t mutually exclusive to their goals.

Sections 5 and 6 are mostly uneventful. They bring up the risk of total state control over an industry in one paragraph and then fail to raise any measure that addresses it. The only person on the EA side who seems to put forth concrete plans to prevent totalitarian risk from AI crackdowns is Roko Mijic, at least as far as I’m aware. Maybe he should be the sixteenth author next time.

Summary

In summary, EAs don’t actually disagree about the order of operations. It is both logistically and legally far easier to restrict hardware than data, research, or trained models. Even knowing the scope and unconstitutional authority necessary to restrict the latter, the authors nonetheless want to restrict them.

Theoretically, a democracy-preserving compromise where there’s thorough, neutral restrictions on hardware, for example through a compute cap, is the best “middle ground” between EAs, accelerations, and AI pluralists. In practice, this will almost certainly not actually happen because of public choice theory. That’s an article for another day.

Can't find anything to disagree with though I'm only moderately well informed. I agree it's a shame that compromises don't seem likely.