It’s the Midwits, Stupid

Linking the holy trinity of Institutional Failure, Polarization, and Wokeism

I found myself spending Monday morning reading Richard Hanania. And once again it looks like we converged on predictively similar models from strikingly different directions. Both insiders and outsiders had long tried to use political models to predict how parties would behave with varying degrees of accuracy; I myself had proposed at least three. So I sat down and got to thinking why we want to do this and what we can reasonably expect to get out of it.

I encourage anyone interested in understanding how the parties work structurally and psychologically to read the original piece, as there’s no way to do it justice in a single paragraph. Since I know not all of you will, I’ll try to do just that anyway. The title of Hanania’s piece is “Liberals Read, Conservatives Watch TV”. He attributes the difference in style, direction, and structure of the Republican and Democratic parties to the preferred medium of the political class, “the community of journalists, activists, informed voters, and politicians on each side.” In his view, the written medium correlates to ideology, persistence, and desire to be seen as virtuous, which drives left-wing political participation. In contrast, television, radio or storytelling more broadly, correlates to a focus on entertainment, profit, and short-term wins, which similarly shapes right-wing politics. He makes plenty of clarifications so whatever obvious “pwn” you’re thinking of probably doesn’t apply. In fact, many of his disclaimers are so good that I’ll be borrowing them for this article too. Here’s his own summary of his article:

There are some straightforward implications of this alignment that Hanania points out:

Liberals are more ideologically driven, while Conservatives are more victory-driven (“own the libs”)*

Liberal tastes are driven by their upper-middle class, Conservative ones by masses or by the market

Liberal lies align with a political message, while Conservative lies are more random

Liberal care more about movements, Conservatives care more about party

*Hanania describes this as tribal, but I would argue that ideology-bordering-on-religion is a form of tribalism as well.

I think that Hanania (and many others) have made a reasonable case that all these downstream effects are both true and significant. You might notice that some of these are corollaries — statements that imply each other. For example, you might not only expect that a written culture values ideology more, but also that a more ideological culture would prefer the written word. This is important because it creates two ways to frame a debate that are both reasonably accurate descriptions of the same set of events.

The next question is obvious: why choose one over the other? In fact, why not choose a different corollary altogether? Bryan Caplan seemed to have that idea. His version is that the left is anti-market, while the right is anti-leftist.

If you’ve followed my writing, or especially the Meta Politics podcast, you might have heard me attempt to pose a similar model. In fact, I’ve proposed something along these lines not once, but three times in an attempt to best describe the problem.

Liberals capture institutions, Conservatives leave and start their own

Parties take turns being ideologically coherent and incoherent

Both parties want to stop having to think about serious problems. Liberals want to hear that something is being done, while Conservatives want to hear that it isn’t a big deal. (I talked about this in some interview that I did that I can’t seem to find now)

My answer to the original question comes from my motivation for thinking about each of these models in the first place. Finding the right model, particularly the correct description of how political parties change, gives us the ability to predict and influence the politics of the future. This gives an answer to the original question that I expect to be fairly reasonable to people of all political stripes: the value of a theory of political parties is that it is predictive and useful.

A Fair Measure

From these two key qualities we can figure out a more systematic way to access our models. Firstly, theories have to predict significant political events, both past and future. They have to be more or less consistent with the idea that Trump won in 2016, Biden won in 2020, that Liberals supported lockdowns and Conservatives opposed them, that the Democratic elite are dominated by cultural progressives rather than economic ones, et cetera. And to ensure that the models aren’t just overfitting, they should be able to make clear predictions about future events and get many of them right.

Take Caplan’s theory for example. At a glance, it is contradictory to our last historical data point. If Liberals hated markets so much, wouldn’t the economic wing of the party dominate? This doesn’t completely debunk his theory though. There are arguments that can be made that range from the historical influence of Marxism on left-wing identitarian movements to HR law being an incredibly effective attack on markets that can extend the theory. While they may be complex and/or counterintuitive, they’re not necessarily wrong either. However, this brings us to our second priority.

Even if Caplan’s theory is technically right about the cultural left, it wouldn’t have been an obvious prediction to make using the information we had twenty years ago. We want a political model that not only makes correct predictions, but makes them very obvious and understandable to the average person. This is also a corrective against overly byzantine and klugey models that can be argued to be more predictive in hindsight, but are routinely “misinterpreted” in practice.

Finally, The Title

So, why midwits? What makes the least interesting people the most important for understanding politics? Well, for one, it’s funny and memorable. However, I’m not just doing this because there are memes about Liberals being midwits, although obviously I wouldn’t be writing this if I think that those memes don’t have at least a grain of truth. There are two crucial implications of this model that are either not implied or not made obvious by the other models I’ve seen:

A highly specific mechanism of action for how institutions are captured and why some institutions are more vulnerable than others

An understanding of how pockets of Republican success are symbiotic with, not oppositional to, left-wing institutional capture

Just keep these endpoints in the back of your mind for now. First let’s go over what we mean by midwit.

A midwit is typically described as someone with 85-115 IQ, although in the case of the political class, it might make sense to adjust this to somewhere closer to 100-120. More colloquially, it describes someone who has slightly-above-average ability in any domain - someone who is able to pass basic qualifications, but is in no way exceptional. Finally, a trait generally associated with midwits is that they are able to follow straightforward instructions very well, but are unable to innovate. Keep this last part in mind, it will be important.

If you’re running a dominant political party, especially one with a bureaucracy, this is exactly the type of person you want to work for you. You prefer a midwit over a dimwit for obvious reasons, with one notable (and very relevant) exception that deserves its own section later. But you also prefer a midwit over an elite* because the latter poses a threat. In many contexts, having a potential challenge to your authority is well worth the value that a more competent person brings. This is rarely the case in incumbent political institutions, as the power structure typically revolves around a system that persists with little intellectual input (and often allows for very little intellectual input to begin with). If you have doubts that this is true, consider the US government. Or any state government. Or any government that has lasted over a century. In many cases the incumbent leaders don’t even understand how the institution was built in the first place. At the same time, elites have agency too. They are more likely to abandon incumbent institutions to work independently, in institutions which are less burdened by historical constraints, or in areas that are dominated by objective rather than subjective measures.

*In this article, we will use elite to refer to high-performers, those above midwits, not necessarily to wielders of political or financial power (although these are clearly correlated).

So far, this is just a shared intuition, but a few examples will make this selection process clear to see in real life. Take the college selection mechanism and pay close attention to whichever major you think is most politically polarizing.

Of course, you might note that the above example only denotes averages. Much like Hanania’s, my model predicts a general trend, not an absolute categorization. There exist some brilliant (and many dim-witted) students in each of these fields. But some, on average, are more skewed towards midwits than others. IQ is also not an all-encompassing measure, but is a reasonable best-for-now heuristic without many alternatives. There are other proxies, such as income or productivity, but those are subject to even more flaws aside from certain ad-hoc cases. We can also use these degree breakdowns to project forward onto industries. For example, software engineering jobs frequently require computer science or mathematics degrees, doctors require medical degrees, etc. Also note that the selection can be applied on the type of work instead of simply the individual. For example, public sector workers had lower military exam scores (a proxy for IQ) than the private sector, but this difference dissipated once professions and demographics were controlled for. Both the type of work you emphasize, as well as the ideological skew, can have significant effects on the selection mechanism, even if the incentives for each individual role stay the same.

If it were simply a matter of correlations, I would still be skeptical of the midwit hypothesis, as I am of the TV/reading hypothesis. The data isn’t phenomenal and many other underlying causes can exist. However, what really gives teeth to this hypothesis in specific categories is their selection systems — systems that explicitly filter out from the top and bottom until you’re expected to end up with midwits. Sometimes this is just done by setting the terms of employment. Job qualifications can filter out candidates from the bottom, while lack of opportunity or compensation direct elites elsewhere. For an even more obvious example, many legacy corporations have compensation and promotion explicitly based on seniority. This doesn’t mean that simply anyone can get or hold such a job, but all employees that can avoid being reprimanded are levelled.

You can also have selection mechanisms that select for elites or dimwits. Tech corporations have a high demand for elite labour and compensate accordingly. They explicitly brand themselves as solving difficult problems in a fast paced environment surrounded by “A-player”(video, more confirmation) colleagues. They engage actively to recruit top talent from universities and have highly selective technical tests. So, they naturally attract not only computer science majors, but also natural science majors, mathematics majors, or iconoclasts who have both the capability and desire to solve abstract and highly technical problems.

In each subgroup of the political class, such as candidates, journalists, staffers, and activists, there is both a lower and upper selection mechanism. You can probably think of plenty more examples in the outside world in which there is both empirical and mechanistic evidence for this type of selection, and odds are those are Liberal too. I will leave these examples out since I’m not writing a 500-page book and I want to narrow the scope to the explicitly political. However, there is one more critically important example.

Ideological Conformity Selects for Midwits

Strict ideological conformity has the exact same selection mechanisms as the aforementioned incumbent institutions, even if the ideology itself is relatively new. It takes some basic amount of ability to learn the mantras and avoid missteps. At the same time, people making correct, well argued, but unorthodox points are shunned for being insufficiently conformist. David Shor was fired for sharing peer-reviewed research to help Democrats win elections. Dorian Abbot had his lecture on fighting climate change cancelled for completely unrelated opinions on admissions systems. Restrictions on freedom of conscience can be a sticking point even if it doesn’t result in an explicit firing or cancellation. This is most frequently the reason given by the most prominent ex-Liberal dissenters, such as Bari Weiss, Peter Boghossian, and Zaid Jilani. This message has drawn large, sympathetic audiences, regardless of whether you agree with their political views or not.

On the empirical side, I haven’t been able to find any direct measures of, for example, IQ by granular ideological faction (in the vein of the hidden tribes report), but there is some indirect evidence. The subjects that are most hot to the touch politically, which are uncoincidentally all outwardly left-leaning, fall neatly into the midwit range: journalism (communication), education, social science, business administration, and yes, “Critical Theory”. However, the completely explicit nature of the ideological selection mechanism, along with the litany of historical examples, makes up for this far and away.

This is in no way a new phenomenon. The historical analogues for this effect are often referred to as “Lysenkoism”, named after Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko was a Soviet “biologist” who rejected well-evidenced genetic findings and made absurd, provably false claims about farming, including but not limited to:

Exposing crops to poor conditions would increase future yield, since “future generations of crops would remember these environmental cues “

Nearby seeds would not cause resource scarcity, since “plants from the same ‘class’ never compete with one another”

Lysenko is the standard bearer for confirmation bias driven pseudoscience. His false claims weren’t at all random, they were what Hanania calls “directional lying”. Lysenko was a devout communist and each of his lies formed part of a coherent argument for communist assumptions. He denied that genes exist, calling them a “barrier to progress”. His third claim above rests on the marxist idea of “class solidarity”. He dismissed the evidence presented by Western scientists, calling them “tools of imperialist oppressors”. With the benefit of hindsight, we know how Lysenkoism ended: his “research” being implemented in the Soviet Union and China was responsible for over 30 million men, women, and children starving to death.

There’s no shortage of this phenomenon in modern times. There’s denial of individual differences in intelligence, supporting baseless “diversity trainings”, making comedically silly correlation equals causation arguments (this one too), denying physical differences based on biological sex, and even calling scientifically rigorous measurement “an instrument of oppression”. Sounds familiar. Of course, not all Democrats hold these beliefs, in the same way that not all Republicans are anti-vaccine or deny the existence of anthropogenic climate change. However, the ability for these beliefs, both left and right, to persist in political, nonprofit, journalistic, and even academic seats of power shows that Lysenkoism is alive and well, even in modern times. The difference between Liberals and Conservatives, as Hanania points out, is organization. As Hanania says,

There are two ways to lie in politics. Let’s say Side A wants to spend more on government, and Side B wants to spend less. Side A might exaggerate the benefits of investing in poor communities, and Side B might tell a story about how tax cuts for the rich will pay for themselves. This can be called directional lying, with each side trying to convince you of something, and this is how politics pretty much worked until the last few years.

Republicans, because they are tribal and not ideological, do not punish their politicians for non-directional lying, or simply making things up … Trump mostly governed like a typical Republican, and his administration pushed for things like less spending on entitlements. Republicans meanwhile have been running ads accusing Democrats of wanting to cut Medicare.

...

Liberals say really false things like “men can get pregnant,” “police are killing large numbers of innocent black men,” and “poor people are more likely to be fat because of food deserts.” Yet these are lies (or more usually, kinds of self-delusion) that you would expect from people who’ve adopted crazy ideological commitments.

The rest of his piece, as well as previous pieces, do a great job of mapping how extraordinary the differences in institutional power are between these two types of ideologies. All of this is to say that evidence-free beliefs are worrying regardless, but are both more influential and more dangerous when organized.

Midwits Select for Ideological Conformity

“A lot of mediocre people love conformity, since it gives them something they can actually compete on”

~Michael Malice

Regardless of your thoughts on Malice, this point is absolutely right. In the previous section, we’ve already gone over the methods in which ideological conformity in institutions selects for midwits. What’s important to understand is that conformity within one institution is neither binary nor static, meaning that the amount of ideological compliance required can range from small trivial actions to significant sacrifices and that the amount can change over time.

An existing model of institutional power describes institutional decisions as a conflict between factions. Then, recruiting, HR policy, and governance is not just a matter of choosing the best person for the job, but rather a matter of choosing the person who would most benefit the faction making the choice. In other words, it’s politics all the way down. With this in mind, ideological conformity and midwit-ry can spread through incumbent institutions fairly easily even without any organized effort. How?

Incumbent institutions disproportionately select for midwits.

The ideologically conformist midwits select for others of the same ideology. This can be done through their hiring decisions, HR law, or employee activism.

The second step is amplified further by incentives, since ideological conformity benefits midwits. They recognize a change in procedures that elevates them over their less conformist, but more productive colleagues.

The increased ideological conformity skews selection further towards midwits, returning us to step 1 where the cycle repeats.

Of course, this cycle also means that incumbent institutions become stagnant or decline at the thing that they were built to do in the first place. In fact, this also benefits midwits by removing elite selection mechanisms. We previously outlined how novelty and demand for skilled labour created a pro-elite culture in tech companies. However, each company was once a startup and almost every company still retains a mix of meritocratic and political selection mechanisms. By undermining a core objective mission and spreading anti-scientific claims when convenient, conformist ideologies can eliminate meritocratic selection mechanisms. This occurs as part of step two in the above process.

This is another mechanism that becomes obvious once you recognize the examples. Why is congress increasingly performative and dysfunctional? Why is there an exponentially increasing amount of college administrators? Why is HR compliance becoming increasingly invasive and punitive, despite evidence that portions of it either do not work or are counterproductive? In fact, Hanania has documented this latter point and made a similar, but less related analysis.

The vast majority of these processes do not occur due to machiavellian planning and produce many side effects that benefit no one, not even the participants in this process. Take the example of the attack on advanced classes and specialized programs, which is occurring in Democrat-dominated areas such as New York City, California, Boston, and Oregon. For the ideology of equality of outcomes between demographic groups, self-proclaimed progressives are seeking to eliminate redistributive, public sector education programs that benefit poor students, immigrants, and asians (examples in New York, New Jersey). In the long term, helping disadvantaged smart kids who may grow up to be elites could be seen as beneficial to midwits, but this type of analysis doesn’t really make much practical sense. If you’ve seen the anti-merit protests, you might guess that they’re driven by emotion rather than deep thinking. To be fair, right-wingers aren’t too different. So, unlike what some prominent right-wingers tend to think, this isn’t really a story about “a plan to take over America”. Instead, it’s a situation where the incentives are aligned so that midwits acting on their own emotional and political biases coincidentally advantage their own political power.

My favorite property of game theory is that while why it works is confusing, how it works is simple to outline, and what it explains is fairly vast. The midwit cycle, my name for the above model, in summary:

Old institutions select for (and are mostly made up of) midwits.

Where there are midwits, ideological conformity spreads faster

Conformity makes everything in old institutions that selects midwits worse

Political change is downstream of the above three points

It also explains the following:

Why everything is Liberal

Why institutions are in decline

(As explained later) Why Republican elites haven’t collectively done anything to change this

The Political Model Megablob

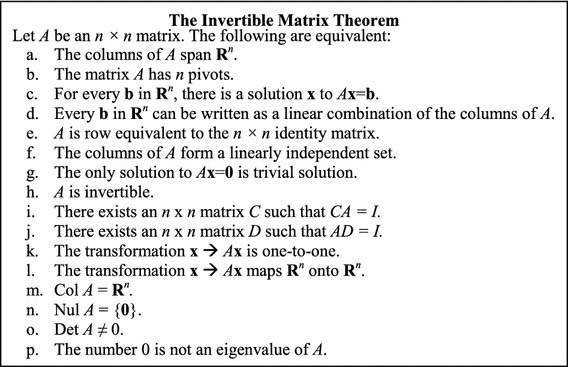

The invertible matrix theorem, a large bundle of equivalent mathematical statements

In almost every field, there is a cluster of ideas that all relate to each other. Take the invertible matrix theorem from my homeland of mathematics. In the case of the IMT, dozens of fairly complicated statements turn out to be exactly identical. Generally, such a cluster denotes some type of underlying order. In my view, this is the case in politics as well. I mentioned earlier that many of these various models are corollaries; there is a high degree of overlap between Read/TV, Ideological/Tribal, Capture/Exit, and Midwits/Non-midwits. Moreover, each of these models strongly imply the others. In that case, it becomes difficult for them to compete on predictive power, as their predictions are highly similar, with maybe a few technical exceptions. Where the models differentiate from each other is utility. I personally prefer the midwit model because it puts the game theory front and center, which makes more things obvious than you would expect. However, as with any bundle, the best part is that you can use the correlations between them to reframe problems in whichever way is most convenient. Hanania’s model emphasizes the persistence of Liberal ideas through time, for example, which can be useful even though each of these models reasonably predict the same thing. That’s why I actively encourage the development and exchange of competing models, particularly within this bundle.

Conservatism is a Market (And Why You Should Blame Them Too)

So, why did I spend so many words emphasizing that this process is emergent and not planned? Simply put, because the current attempts to address this problem are failing. It’s actually much easier to reverse the consequences of an organized plan than an emergent process. Simply remove the leaders from power and wield political force. So far, that’s exactly what Republicans have been trying to do.

A map of passed and proposed anti-CRT laws

They put Trump (and just now, Glenn Youngkin) into office. They passed broad anti-”Critical Race Theory” (CRT) laws, which some have criticized for being illiberal. They threatened to break up companies and have proposed legislation to make it easier. As Marhsall Kosloff said on the Realignment podcast, “It doesn’t matter if you break up Google or Amazon. Each of those new companies will still be managed by people who would censor Donald Trump”. Similar arguments are easily made for other Republican approaches. Even if anti-CRT laws are passed, left-wingers who would have taught it have plenty of other ideologies to choose from. Trump radicalized left-wing movements (although other Republicans, like Youngkin, may not). While some of these efforts may change exactly what issues are being fought over, and it’s fine for conservatives to see that as a victory, it doesn’t change the underlying dynamic at play, in which the average institution inevitably creeps towards the left and towards decline. So, do I believe Republican elites are just stupid? Are they just incapable of reversing this trend, or at the very least the parts that disadvantage them?

No. The Republican party is a market, and the ones who make the right bets are perfectly fine.

Firstly, elites can shelter themselves. Anyone in at least the upper-middle class (>$200000/y) can find a private school and pathway for their children that avoids whatever problems the midwit movements cause. More importantly, the US is a two-party system, which means that Republican coalitions get the inverse of what Democratic coalitions get. Earlier I said that there was one very important exception to the idea that you would always prefer midwits to dimwits in a political movement. As Ross Douthat wrote in reaction to Hanania’s piece,

I generally agree with Hanania’s (and many others’) observation that the Republican party is at its core a market for Lib-dunking. It allows whoever is most skilled, industrious, wealthy and attuned to the base to take control of the party. Control over the Republican party essentially falls to whoever makes the best bets on their base and allows the victor to implement their policy of choice, within reasonable limits. This precisely describes the state of the Republican party post-Reagan, and accounts for the exceptions in Hanania’s model. This piece is already getting quite long, so I won’t really linger on the ethics of this arrangement other than to say it makes it highly unlikely that the Republican party will solve the midwit cycle.

Forward And Up

Aside from the selection mechanism and the Republican incentives corollary, I would say the most important takeaway from this model is that the status quo is incredibly stable. By that I don’t mean that the issues being debated won’t change, that polarization won’t increase, or that elected offices won’t continue flipping back and forth. Instead, the incentives and institutions that cause this cycle in the first place will continue to exist and self-perpetuate, despite the efforts of Hanania, third parties, or intellectual movements. They will continue to exist despite the efforts of entrepreneurial right-wingers. They will continue to exist despite left-wing dissidents. They will continue to exist despite a challenge from popularism, economic changes, or Trump. None of the existing challengers to the status quo change the underlying selection mechanism. This isn’t just because no smart people have tried to solve the problem. The cycle perpetuates because it is an incredibly resistant set of decentralized incentives that has built-in reactions to the most common challenges to it. In my opinion, the most significant mistake of both the “anti-woke”, “depolarization”, and “never-Trump” factions is underestimating the things that they want to fight.

So, what do we do about it? I only have two broad suggestions that I want to emphasize in this piece. One practical measure within an institution is to emphasize objective measures and eliminate cases of “failing up” — granting additional power to employees either because of or despite a poor track record. Stronger selection mechanisms produce elite, rather than midwit culture. Of course, this is practically challenging in most areas due to the tautological scarcity of exceptional people. The second suggestion is to ensure that firm institutions with clear center, right-wing, or apolitical rules exist. Ideological selection will inevitably happen in most institutions, but firm, unwavering rules and principles can prevent polarization from becoming significant or inducing capture. Meanwhile, you still need to be able to employ midwits as part of a bureaucracy to maintain large, powerful institutions. This, too, is no easy feat.

Seeking a way out is another alternative. Striking out on your own, founding a new company, or founding a new country are alternatives at different scales. In this article, I’ve taken for granted that the existing political system should be saved. I do think this is a period of technological and social change where that assumption should be questioned. My next article of this length will likely be on whether institutions relying on the assumption that human beings have equal potential can coexist with technology that clearly disproves it.

At this point, I just want to offer the best of luck to anyone with the passion, ability, and determination to attempt a change, whatever it may be.

Possible reference for “failing up” or "heads I win tails you lose": https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2011/10/14/the-gervais-principle-v-heads-i-win-tails-you-lose/