Just Add Points for Republicans

The Hubris of “Scientific” Polling Corrections

Imagine there is a special place you can only communicate with every four years. Let’s say it’s Alaska. Every four years, you send a crew of people to Alaska and they return with a simple survey. They tell you which of two figures they want to rule America, and by extension Alaska.

Let’s say you wanted to predict what these Alaskans would choose. At your disposal are extremely powerful tools of observation for every other state in the union. You can poll to high precision and accuracy what everyone else thinks. And you wish to use that information to figure out what Alaskans want. One year, your results are off fairly dramatically. You were extremely confident about Alaskans voting for A, and Alaskans went for B. What would you try to do?

Perhaps you would send more ships to Alaska. Maybe you would hire some correspondents. But if those were off the table, the overwhelming intuitive idea would be to say that Alaskans will probably differ from the rest of America by around the same amount they did before.

Of course, this is an extended analogy about polling. How polling works is that polling firms use online and telephone surveys to predict how the US will vote every four years. The problem is that these outreach techniques can only reach a very limited set of people. Polling response rates vary slightly, but they all tend to sit under 10 percent. The analogy I used is somewhat backwards: it’s less like trying to measure Alaska from the mainland and more like trying to measure the mainland from Alaska. Not an easy task.

Pollsters might say this isn’t a fair comparison. “We try to make the sample representative”. In other words, Alaska has very tight borders. Alaska only lets in the right people. And by that we mean that Alaska lets in people with roughly the same proportions of race, sex, education level, and sometimes other characteristics like income. But they are still all people who want to move to Alaska.

Are polls honest about where they go wrong? Statistics react to power like phosphorus reacts to air.

This is why I have this extended analogy to hopefully help more people “grasp” the main ideas, even if it’ll annoy some statisticians who think I’m simply being lazy.

Polls usually report something called a confidence interval. It’s a statistical indicator of how likely they are to be wrong. What does this measure? Let’s say you tried this Alaska experiment all over again, and chose some new Alaskan immigrants with exactly the same rules. The confidence interval measures how likely it is that you’d get the same results. In other words, they measure how similar your Alaska is to Alaskas in parallel universes. With enough money, you can get this number down quite significantly. It’s an easy measure to optimize. This correction, the correction for essentially random error, is what makes a survey legitimate, scientific, and meaningful.

Does it quantify anything remotely meaningful about whether the “representative” Alaskans will vote the same way as mainlanders? Nope. None at all. This is quite important, because if you think about it, your intuition will lead you to think that the primary reason why you get an error is not because Alaska differs from what you’d normally get applying the same border controls, but because people who want to move to Alaska just aren’t really like most Americans in the first place. Is there a statistic that tells us about that?

We measure this error every four years (well technically two, but midterms are quite different). It seems to be steadily getting worse, so we should find some way of fixing it. How do we fix it, you might ask? First, we’re going to take the group of Alaskans we were the least wrong about (or were wrong about in the opposite direction). Then we’re going to make sure that we let in more Alaskans like them.* This is what is being done when you re-weight polls by, for example, education. Our polls said that people without college degrees vote Republican more, and our polls overestimate the Democrats, so let’s get more people without college degrees.

Intuitively, this seems like a good idea. In many circumstances it is. But let’s take another analogy to explain why it can fall apart. You have a room full of people, each representing a certain demographic (combinations of age, sex, college, etc. as described above). All of them, on average, lie about voting more for Democrats, but some of them lie less than others (non-college voters). Then, the next time we do the survey, we’re going to ask the non-liars more and the liars less.

It is correct that this will reduce the amount of lying (which in real life can be all forms of bias, not just lying). But what it also does is fill the room with honest people. All of this is fine if the rate of lying stays the same. Your readjusted room is closer to America. What if the rate of lying changes? Well, you’ve just filled your room with honest people. If the rate of lying increases, you’ve hedged yourself against further bias (although you will nonetheless get an increase in bias). But what if the lying decreases? What if Trump is an isolated phenomenon? You’ve now opened yourself up to a whole different sampling problem, still underestimating Republicans.

The point of this piece is not that pollsters should give up on trying to make better guesses. The point is that every approach has its tradeoffs and it's very difficult to predict which way those tradeoffs will actually go. Given that every sampling reweighting has its own extraneous consequences, what would I do to correct it?

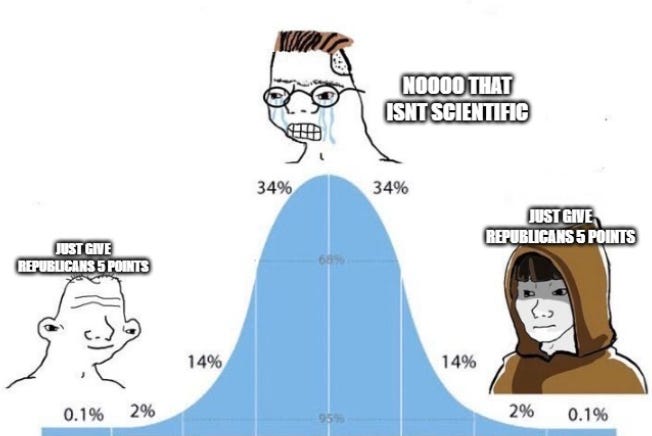

I would simply poll the same way and add the previous election’s polling bias.

That’s it. There are scenarios where the political environment is more stable that could convince me otherwise. But that isn’t the present. This is the solution that just can’t be named in an official polling firm. It isn’t “scientific”. “What, you’re just going to add a bonus to Republicans? How unsophisticated”. It’s fairly easy to argue that adding the previous polling bias is the mean of what we can expect when we’re still too far in advance of the next election of what it would happen and therefore minimizes least squares across the different ways Alaska and America could diverge in the future. In fact, that’s the argument which makes the fewest arbitrary assumptions and is obviously at least one contender to be the strongest.

But it also strikes exactly through the hubris of the polling mythos. It requires admitting constraint. Admitting uncertainty in a way that the proles would understand. That would not be very scientific of you, despite the exact same boilerplate mathematical arguments as every other paper. You can probably tell I don’t think this is a useful way of solving the actual problems with polling. Sometimes, you just have to keep things simple.

* Pollsters would say that they’re reweighting polls to be more reflective, not just simply to add more Republicans who tell pollsters they’re Republicans. “We were genuinely undercounting the non-college vote before”. This is true, but there’s no reason to think that if you average across all controlling variables that honest Republicans are actually undersampled, so by selective choosing variables to control for which increase the sampling of honest Republicans, you’re just creating a justification to add more honest Republicans. Note that this is true even if the specific variable in question is genuinely undersampled (i.e. this is not a p-hacking argument).

Or perhaps Republicans have found their own way to 'stick it to the man.'

Thanks for the post.

"It’s fairly easy to argue that adding the previous polling bias is the mean of what we can expect when we’re still too far in advance of the next election of what it would happen and therefore minimizes least squares across the different ways Alaska and America could diverge in the future."

Could you be a bit more precise about this? I don't really understand what you mean.

Based on the results in the table, previous bias doesn't seem to predict the magnitude or direction of future bias well at all (in fact, simply adding as you suggest would lead to worse predictions more often than not).

I also think I disagree with your overall criticism of pollsters pretending to be scientific. More than most areas, polling seems like a field where the proof is in the pudding, and nobody denies the subjectivity of modelling decisions. The sheer fact there are a variety of different polling companies who claim to be more accurate than each other suggests that this is well understood.

I also think it's important to take into account the fact that the business model of polling companies relies on them being able to sample public opinion on a range of different things, not just predict elections. Elections are where their methods are publicly tested, but if they're systematically missing some of the population, then fudging the numbers as you suggest might give a good prediction, but it won't be much good when Kellogg's need to understand the impact of their new marketing campaign for Cornflakes.